Dyeing with Cochineal,

or

The Author as Alchemist

Freshly Dyed Silk

To anyone who loves color as much as I do, the dyer's art seems like pure magic. How else to describe the alchemy that transforms drab cloth into banners of blazing red, subtle purple, and shimmering blue and green? In writing A Perfect Red, I had a chance to learn some of the mysteries of color at first-hand — and even learn a few alchemists' secrets along the way.

My Grandfather at Work

I am the granddaughter and great-granddaughter of dyers, but when I started researching the history of cochineal, my personal knowledge of the dyer's craft was woefully threadbare. Tie-dyeing T-shirts and creating elaborate Easter eggs was the limit of my expertise. Yet the more I learned about dyers and dyeing, the more I wanted to know.

"The dier... in smoke, and heate doth toile, / Mennes fickle mines to please," runs a Renaissance poem. I wanted to experience the smoke and the heat and the steam and the smell of the dyer's workshop. What was it like to dunk the dull fabric into the simmering pot, then haul the sodden cloth out again, full of dazzling color?

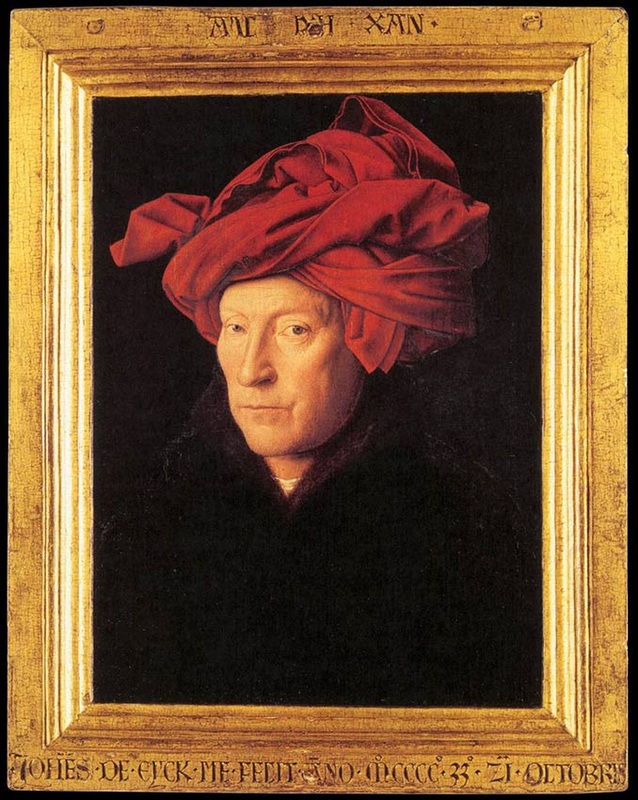

To better understand the dyer's art, I decided to try my hand at making a Drebbel scarlet, a color that many people in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries considered a perfect red. It was named for its discoverer, Cornelis Drebbel, a Dutch inventor and alchemist who lived in London in the early 1600s.

According to some stories, Drebbel's discovery was a complete accident, the result of some tin and aqua regia falling into a bowl of water dyed with cochineal. But I suspect Drebbel actually stumbled across the new dye during his alchemy experiments. Tin and aqua regia (a combination of nitric and hydrochloric acids) were often used in alchemy. Alchemists worked with red dyestuffs like cochineal, too, because red was the color of the fabled philosopher's stone — the mythical substance that was supposed to transmute base metals into gold and bestow eternal life on its creator.

However he came across it, Drebbel's scarlet dye was sensationally bright, producing the most brilliant red cloth ever seen in Europe. With further experimentation, Drebbel seems to have discovered that the key ingredients were tin and cochineal, combined in the presence of an acid. (Aqua regia, as it happened, was too powerful an acid for dyeing cloth — it tended to eat away at the fabric — but other, much weaker acids turned out to be very effective.) According to the English chemist Robert Boyle, the new cochineal dye produced "a perfect Scarlet."

By the mid-1600s, other European master dyers had figured out Drebbel's secret, and they used tin, cochineal, and acidic compounds in various formulations to produce a range of luminous scarlets, from a deep cherry red to an eye-popping neon color. The most brilliant reds were "full of fire," according to one observer, "and of a brightness which dazzles the eye."

Together, these variations on Drebbel scarlet took Europe by storm. No other red dye was so bright, and no other dye seemed so desirable. Throughout the continent, Drebbel scarlet was incorporated into court robes and fashionable gowns and rich tapestries, prized especially by the flamboyant court of the Sun King, Louis XIV, and by the cavaliers of riotous Restoration England. But the new red also served more serious purposes, too. Blankets colored with the dye became a staple in the North American fur trade, while a version of Drebbel scarlet became the red in the coats of British Army officers, the uniforms of Russia's Imperial Guard, and the kilts of Scots warriors.

Little wonder, then, that of all the colors I read about while researching A Perfect Red, Drebbel scarlet was the one I most wanted to try making myself.

The Art and Craft

of Natural Dyeing

To follow in Drebbel's footsteps, I needed some recipes. In my research, I had already come across several very old ones, but their instructions and ingredient lists were often contradictory or unclear, so I looked to the books of two modern dyers — J. N. Liles, author of The Art and Craft of Natural Dyeing, and Gosta Sandberg, author of The Red Dyes — for additional advice. After reading through all these materials, I selected a Liles recipe ("Cochineal Scarlet Recipe No. 1: Silk") as the basis for my first attempt at a Drebbel scarlet.

Cochineal, Cream of Tartar, and Tin

Next I went looking for cochineal and some fabric, as well as the natural mordants that would help the color stick firmly to the cloth. Because I'm allergic to wool, I chose to dye silk — a fabric that works well with Drebbel scarlet dyes. Thanks to the knowledgeable and generous community at the Natural Dyes listserv on Yahoo, I soon found good sources for all the materials I needed.

In the Lab with My Dad

Although some natural dyes are safe enough to use in the house, the tin in Drebbel scarlet is a hazardous metal, and the vapor that rises from the dyepot can cause health problems. Fortunately, my dad is a scientist, and he offered me space in a chemistry lab, where fumes from dyeing could be safely ventilated. To prepare for the dyeing session, I washed my undyed silk scarves with a gentle soap and lots of hot water, a process known to dyers as scouring.

Mortar and Pestle

During my next vacation, I set up the lab with the help of my dad and my husband. I started by putting the scarves into distilled water, wetting out the cloth so that it would take the dye up more evenly. Next we poured a gallon or two of distilled water into the dyepots and put them on burners. (Both glass and stainless steel vessels work well as dyepots, because they don't react with the different dye chemicals.) While pots heated up, I weighed the cochineal and ground it to fine powder with a pestle and mortar. I also measured out tin and cream of tartar, a weak acid often used in the making of Drebbel scarlet.

Adding Cochineal to Water

I tossed the cochineal into the simmering dyepot, and it flooded the water with a glorious red color. When I added the tin and cream of tartar and stirred, the water turned a dark ruby red. The steam rising from the dyepot smelled curiously acrid and salty, and I could taste it in the back of my mouth before it disappeared into the lab's ventilating hood. We cooked the dye for a while longer, keeping it a bit below boiling. As I stirred, the damp heat from the dyepot reddened my cheeks and curled my hair.

Adding Silk to the Dyepot

After about half an hour, we added the first piece of wetted-out silk. Gradually it soaked up the color, turning first pink and then salmon-rose and then a bright, rich red. We kept it in the pot for over twenty minutes, stirring it frequently. (Gianventura Rosetti, author of a 16th century dyers' manual, recommended that dyers keep the fabric moving to get the best color. "Put in your silk and go turning it over in the water," one of his recipes advises. "Keep it under, and turn under and upward.")

Rinsing the Silk

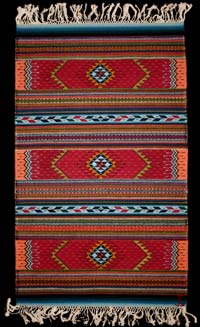

When the silk was ready, I ladled the fabric out of the pot, then unfolded it and dipped it back into the hot liquid to wash the fragments of cochineal away. The silk glowed in the light, a brilliant red. We rinsed it carefully in distilled water, then set it out on a towel. The silk lightened slightly as it dried, but it still remained a brilliant scarlet — almost a neon red, far brighter than I'd ever expected it to be.

We spent the rest of the afternoon dyeing the remaining silk. Only in the very last batches, after most of the cochineal and mordants had been used up, did the color become noticeably paler — a lovely and intense shade of salmon pink.

Drying the Silk

At the very end of the day, we recreated the reaction that is thought to have inspired Drebbel to create his scarlet dye. We boiled some cochineal in a basin of water till it had turned a dark violet color, then suited up in goggles and aprons. As the liquid cooled, we held a piece of tin above it and spilled a few drops of aqua regia onto the tin.

The response was immediate and explosive: the metal disappeared where the acid bit into it, leaving behind only a puff of dark smoke and a few drops of aqua regia mixed with liquid tin. When these drops fell into the basin, the cochineal water turned a dazzling red.

It was an impressive display of alchemical fireworks. We dropped a little more aqua regia onto the tin, just for the fun of seeing the kick and fire of the chemical reaction.

The real magic, however, was in the dyeing itself. At the end of the day, I was still a novice in the dyer's world, but I had experienced what books could not convey: the pungent smell of the seething dyepot; the sleekness of damp silk against my skin. Under my gaze, meek white scarves had blossomed into banners of shimmering red silk — the "perfect Scarlet" that centuries ago had dazzled the eyes of alchemists, poets, and kings.

By nightfall, even my hands themselves had been transformed. Like dyer's hands of old, they were saturated with red dye, each fingertip stained scarlet, vivid proof that I was no longer a stranger to the craft of color.

Dyer's Hands